de page

D A F N E

A Modern Madrigal

Wolfgang Mitterer, composition

Geoffroy Jourdain, musical direction

Aurélien Bory, Stage direction and scenography

DAFNE : A MYTH

STAGING

Dafne is the story of a loss. Apollo is the main, unhappy hero of this. He is the god who conquered Python, the god of oracles, the radiant god, the god who directs all the Muses, the god with the golden lyre – this god is rejected by Daphne. Apollo, because of his pride, is conquered by Cupid. In order to escape him, Daphne is transformed into a laurel bush. A strange fate for the most beautiful of the nymphs, she who wishes to escape from procreation and remain independant, fleeing through the woods – a hunter hunted by the twisted god – a strange fate to be changed into a tree, so not able to flee her attacker anymore, but still escaping him physically. In this frantic flight, Daphne achieves the ultimate escape, a metaphysical translation – from a gendered animal to an asexual tree, escaping bestiality by being elevated to a higher realm, as Opitz writes in his introduction: “what Daphne offers is eternal”.

Apollo bows his head and decides to bear his loss. He proudly wears his laurel wreath. Later, poets and musicians will do the same, as a sign of love. The fact that this work is lost, so that we will never know how it sounded, is, of course, hard. But I like the idea that art responds to loss. Isn’t it the role of creation to continue the translation, the transformation? Isn’t it a principle of art that it inserts itself into the traces of the past and allows them to slip into a new, unpublished work? It is this idea that supported Geoffroy Jourdain when he suggested to Wolfgang Mitterer that he should write music for this libretto, as an echo of Schütz’s work. In Dafne, Echo’s first words responding to the shepherd’s worrying are “Hier, Hin, Ich” – “I’m going”.

The idea of a classical chorus from which all the roles would stem especially interested me. In Daphne’s struggle for freedom and independance, her fight and the transformation are the principal motifs of the myth, as well as the challenges of the scene. The vocal group slips from one role to another, from a group to an individual, from a voice to an instrument; electronic sounds in physical space intersect with the myth of Daphne and the passage of the madrigal-style song to the dramatic song at the beginning of the 17th century, and finally the text which is being transformed from Ovid to Opitz via Rinuccini. All these scenic effects are thought through as seen on the stage and implemented by the group of singers: from the stalking of Python to that of Daphne before her final metamorphosis into a laurel bush. And with these singers-actors-musicians-props operatives in constant transformation, would we not experience something that escapes us, like the ultimate escape of Daphne, the eternal rebel?

SCENOGRAPHY

Aurélien Bory

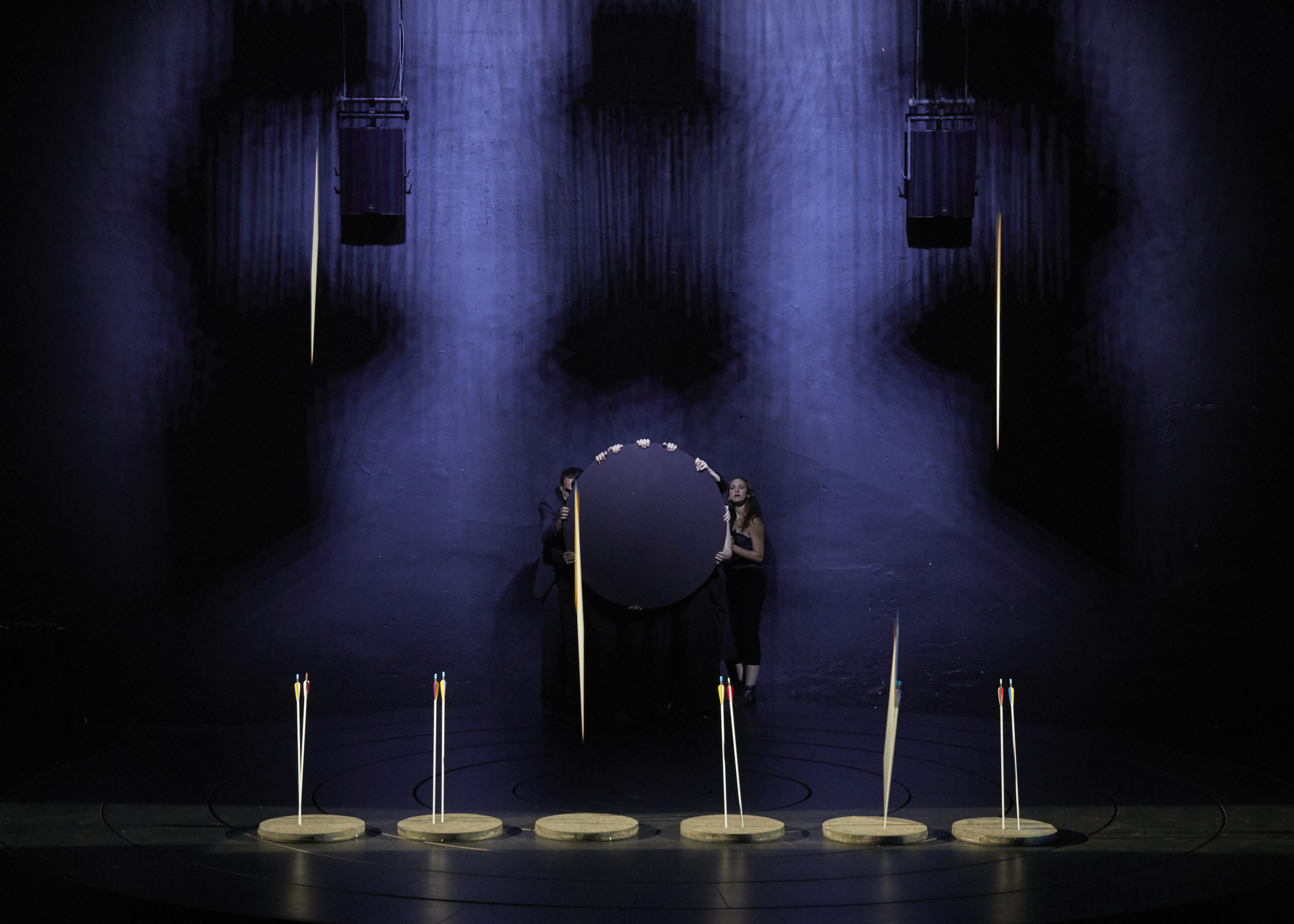

The central point, which is at the basis of rhe myth of Daphne, is her metamorphosis into a tree. So – how is a tree formed? It forms along its axis, then develops towards the outside, forming rings – the lines visible in the cross section of a trunk – where the sap circulates, unlike its heartwood, the hardest part. When Daphne is transformed into a tree, it is the same process – a hardened heart that is protected from attack from the outside. I envisage the scene like the cross-section of a tree; a staging composed of concentric rings – six rings around the central part – like lines forming a revolving and multiple stage, with each ring able to turn independently of the others.

In addition to the possibility of composing a visual polyphony, with each singer being placed on a circle and turning in harmony, in unison or in counterpoint to the others and to the musical composition, this would make the mobile-immobile chorus into an ever-changing perspective, with the turning rings offering numerous choreographic possibilities for Daphne fleeing, Cupid’s flight, Apollo’s battle with Python – especially employing the principle of breaking down the movements.

The initial inspiration for this staging is the anatomy of the tree, but the theatre as a tool has a very strong infuence here. Revolving stages have long inspired stage artistes, from the western theatre to the far-eastern Japanese Kabuki theatre, even including the theatrical facilities — notably in Germany — of the 19th century. However, the first revolving stage appeared in France, invented by an Italian engineer Tommaso Francini for Queen Marie de’ Medicis in 1617. This was barely 10 years before the creation of Schütz’s Dafne.

The multiple rotations — revolutions, I should say — around the central area resonate with the theory of physicist Johannes Kepler, whose book Harmonices Mundi, written during the same period — in 1619 in Linz — describes the elliptical movement of the planets, and establishes a correlation with musical notes, following the idea that harmonic order has its origin in the movement of heavenly bodies. Kepler forms a celestial choir of six planets — Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn — a number picked up here in the staging with its six rings.

Thus I envisage in this staging elements which refer both to the myth and the understanding of the universe in Schütz’s day. The revolving stage, important scenography in the history of the theatre, invented by transforming the unchanging space of the theatre, supports the metamorphosis through which we lose Daphne, but which makes her cyclical and eternal.

Presentation of the project

Geoffroy Jourdain / Les Cris de Paris

When I suggested to Wolfgang Mitterer that he read the libretto, he was immediately taken with the idea of composing a new Dafne for singers and electronic music; an opera on the subject of metamorphoses – that of Daphne, of course, but also that of words into singing, singing into polyphony, and polyphony into the mesh of electronic sounds. The metamorphosis of Schütz’s language into that of Mitterer would raise the ghosts of this music that went up in smoke in the 17th century, and at the same time, would revive once again the two thousand-year-old dramatic power of Ovid’s poem.

We quickly planned the general shape of the musical project: thirteen singers would use the electronic music immersively, like a continuo. They would tell the story and play parts in turn – now collectively, now individually, fulfilling the various functions of the theatrical action: as narrators, spectators, commentators and, of course, as the protagonists (Ovid, Apollo, Venus, Love, the Daphnes, the shepherds) of this tragicomedy, expressed as a vast modern madrigal, beyond opera and its codes.

Thanks to the translation work carried out for us by Elisabeth Rothmund, a French specialist in Baroque German poetry, Wolfgang, Aurélien and I worked together closely on the libretto and dramaturgy. Together, we refined the concept of the network of processes involved in writing music (solo and group singing, refrains, repeats, etc) where each technique, as it affects or stimulates the others, contributes to the action and the understanding of the drama. We chose to make the musical composition fit the bill of a “bespoke” composition for a specific group of performers, taking account of the individual vocal abilities of each, and also of their qualities as instrumentalists.

Our reflections together on the varying dimension of time where, in each historical object, all periods are tangled together and fantasies collide, go on to contribute to the concept of this contemporary opera daily. Questions from our period on the power of Nature faced with the blindest impulses resonate there, and our fascination for this modern heroine comes into focus there. By her transfiguration, she avoids all forms of submission, including the passage of time. Daphne is a symbol of an ideal of absolute beauty, because she escapes from her pursuer. Through her metamorphosis, she invites us to meditate on the impossibility of satisfying the artistic quest.

The creation of Dafne will take place in 2022, the 350th anniversary of Heinrich Schütz’s death.

DISTRIBUTION

With Les Cris de Paris

Adèle Carlier : soprano

Anne-Emmanuelle Davy : soprano

Michiko Takahashi : soprano

Amandine Trenc : soprano

Jeanne Dumat : mezzo-soprano

Floriane Hasler : mezzo-soprano

Clotilde Cantau : mezzo-soprano

Safir Behloul : tenor

Constantin Goubet : tenor

Mathieu Dubroca : barytone

Virgile Ancely : barytone-bass

Renaud Brès : barytone-bass

Conception Geoffroy Jourdain, Aurélien Bory, Wolfgang Mitterer

Composition Wolfgang Mitterer

Musical direction Geoffroy Jourdain

Stage direction and scenography Aurélien Bory

Staging assistance Gabrielle Maris Victorin

Artistic and technical collaborator Stéphane Dardé

Decor Pierre Dequivre

Light creation Arno Veyrat

Costume designer Alain Blanchot

technical manager Thomas

Stage operator Thomas Dupeyron, Mike Godbille

Sound Engineer La Muse en Circuit

PRODUCTION

Les Cris de Paris – Geoffroy Jourdain | Compagnie 111 – Aurélien Bory

COPRODUCTION

Opéra de Reims, Atelier lyrique de Tourcoing, Opéra de Dijon,

Théâtre du Capitole – Toulouse, La Muse en circuit – Centre National de Création musicale,

Points Communs – Nouvelle Scène nationale de Cergy Pontoise – Val d’Oise

Supports (in progress)

Dafne is supported by : the Lyric Creation Fund, exceptional aid to independent theatrical teams – DGCA/DRAC Occitanie, aid for the writing of original musical works – Ministère de la Culture/DRAC Île-de-France, the Centre national de la Musique, aid for the creation of the Mairie de Toulouse, and SPEDIDAM. Commissioned by the Cris de Paris from Wolfgang Mitterer with the support of the Fondation Ernst von Siemens pour la Musique