de page

Azimuth

Sidi Ahmed or Moussa

(creation 2013)

Freely based on the figure of

Moroccan acrobats are called “the children of Sidi Ahmed Or Moussa”. He was an eminent 16th century Sufi thinker, whose grave has become a pilgrimage shrine. He is regarded as the Patron Saint of Moroccan acrobatics. Initially, these acrobatics performances are not considered as being a part of the performing arts; they are closely related to Soufism, they emerged from ancient Berber ritual practices and they consist of circular and pyramidal stunts, in which I perceive both celestial and maternal representations.

The Paths

In Sufism, an ontological quest, the concept of the path is essential. Azimut (Azimuth in English) derives from the Arabic As-samt (Sumūt in the plural), meaning “the paths”. Azimut is the term used in astronomy to describe the angle between the observer and the celestial bodies. With this meaning, the sky is summoned.

In the legend of Sidi Ahmed Or Moussa, when the wise man reached the heavens, he looked back at Earth and men, and settled upon going back. Among others, his path led me to embrace the return motif as the core of the writing.

I liked the idea of the return to mother-earth, a return where birth and death are intermingled; by its very nature, a return used as the compass of life. I like pondering these verses by T.S. Eliot :

« We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started… »

Aurélien Bory, September 2013

Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa experienced some kind of celestial assumption, yet chose to go back to earthly life. It seemed to me that his path was a beautiful metaphor for the work of the acrobat.

Aurélien Bory in an Interview conducted by Catherine Blondeau (Grand T à Nantes) Oct. 2013

(…) He who would learn to fly one day must first learn to stand and walk and run and climb and dance; one cannot fly into flying.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Interview of Aurélien Bory

Conducted by Catherine Blondeau, director, Grand T Nantes, October 2013

What reasons led you to go back to work with the Groupe Acrobatique de Tanger (Tangiers Acrobatics Group)?

It is a recurrence indeed, and it is not customary for me to double back. But we have shared a very strong history, and I spontaneously wished for this reunion. Perhaps Taoub had not expressed everything yet? Moroccan acrobatics is a jewel, and I aspired to take our confluence further. Azimut would not have been conceivable ten years ago. It took us all these meanderings to get there, to produce such a piece.

You mention acrobatics, let’s talk about it: its presence is scarce in Azimut; was it a starting point for the creation?

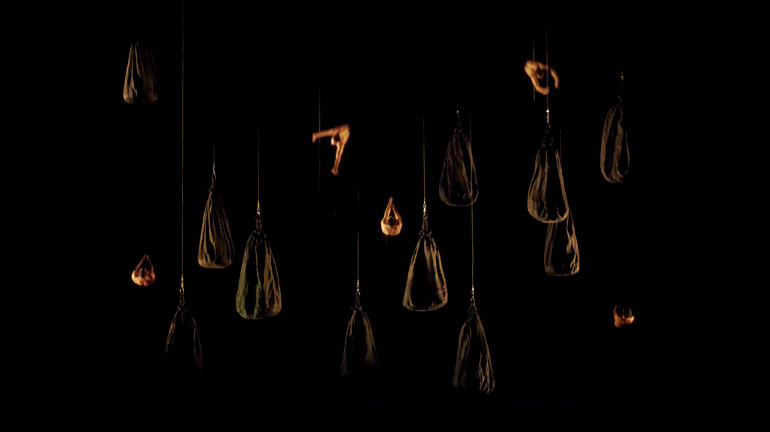

On the contrary, acrobatics are everywhere in Azimut, maybe not explicitly in their familiar forms, but through their deepest roots, specifically in the aerial figures. The concept of flight was my starting point. Over and over, an acrobat’s jump is a failed attempt at flying. The flight is a stage machinery as well. Hence the constant dialog with gravity, bolstered up by the counterweights, the wires and the suspended bodies.

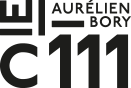

Azimut dwells in an enigmatic chiaroscuro, from which images emerge like apparitions. Is “gravity” hereby summoned?

Before anything else I wanted for these apparitions to be startling. The dramaturgy in Azimut is bathed in profound, spiritual and existential reflections. Moroccan acrobatics are intimately intertwined to Sufism through their tutelary spirit, the patron-saint Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa. My intent was not to tell his story, but it was an inspiration. Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa experienced some kind of celestial assumption, yet chose to go back to earthly life. It seemed to me that his path was a beautiful metaphor for the work of the acrobat.

The trajectory of the Groupe Acrobatique de Tanger is remarkable and unforeseen: from the Tangiers beaches to stages all around the world. What is your outlook on this unfolding?

I bear in mind that this is a two-way emancipation movement. It could not have been predicted that the descendants of the Hammich family, who has instructed acrobats in the heart of the medina of Tangiers for seven generations, were to encounter contemporary art, and thus cast a new outlook on their performances. I am glad that Azimut may contribute to their non-characterization to a definite role of either “acrobat” or “Moroccan”. And I am ready to bet that the dismissal of the usual clichés releases our own outlook and cross-examines our own emancipation.

Aurélien Bory Goes To Tangiers

03 June 2014

Beautiful, soft and mysterious, this is a performance that leaves you speechless, but also makes you want to talk about it, while managing both to soothe and pack a punch. Azimut, directed by Aurélien Bory for the Groupe Acrobatique de Tanger [acrobatic group of Tangiers], has all of the ingredients for invention and emotion without ever overdoing it when it comes to the multiple scenes that he makes unfold.

And yet there is an avalanche of scenes, each one more admirable than the last. Bodies fall and rise, appear and disappear. Levitation is the key word of this stage, where accessories and performers form a strange unit, relying on obscurity to keep their sophisticated technical underside hidden.

The spectacular supernatural world of Azimut, with its shadows, ghosts and spirits, perfectly serves the cause of the irrational and of magical thinking, such as they flow through everyday life in Morocco. They find an unusual outlet between circus, theatre and live music in this family-friendly ceremony. In the footsteps of Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa, a 15th century Sufi sage and patron saint of Moroccan acrobats, Azimut (from the Arabic as-samt, meaning “path”), as its title indicates, has walked the path while exploring its rather more eccentric side (azimuté in Bory’s mother tongue means to be crazy, mad).

The impact of this group of acrobats of nine men and one woman – a second woman takes part in the performance without directly participating in the circus figures – shines in the misleadingly simple human constructions. A chain of people climb up onto each other’s shoulders and end by weaving a never-ending garland; bodies are bound together to face up to the challenge. Accompanied by two singers and traditional musicians, all of Azimut’s human architecture, both massive and vulnerable, conveys a community, its weight, its protection, and an enveloping cocoon.

The basic principles of Aurélien Bory’s work provide an interesting point of focus. The director’s addiction to weighty stage design has become one of his calling cards. A mobile wall supported Plan B (2003), much as the fabric of a circus tent did for Géométrie de caoutchouc (2011)… Here he has devised a metal grill, a hypnotic criss-cross suspended at the back of the stage that makes all of his strategies possible. The only other thing he needs is quite simply a forest of cables that vibrate in the dark to illuminate a fire of sensations.

Is it the humanity and culture of Moroccan acrobats that breathed such life into the work of Aurélien Bory? He has already proven, in shows dedicated to performers such as Erection (2003) for Pierre Rigal and Plexus (2012) for Kaori Ito, that he knows, with empathy, how to amplify the talent of others while strengthening his own writing.

Aurélien Bory met the acrobats of Tangiers in 2003, three years after the creation of his Toulouse-based theatre company. With them he staged Taoub (2004) to great public acclaim. Azimut seems to be following suit. Tightly entwined with the Hammich family, whose members have been acrobats for seven generations, this is a significant milestone for the troupe. Bory likes to say that “this collaboration is the incarnation of Baraka. For those who have been touring the world for ten years; and for me because this encounter has taken a huge place in my life”.

Rosita Boisseau

distribution

Design, scénography and direction Aurélien Bory

With the artists of Groupe acrobatique de Tanger Mustapha Aït Ouarakmane, Mohammed Hammich, Amal Hammich, Yassine Srasi, Achraf Mohammed Châaban, Adel Châaban, Abdelaziz El Haddad, Samir Lâaroussi, Younes Yemlahi, Jamila Abdellaoui

And the singers Najib El Maïmouni Idrissi, Raïs Mohand

Chief of Groupe acrobatique de Tanger until june 2015 Younes Hammich

Director of Groupe acrobatique de Tanger Sanae El Kamouni

Light design Arno Veyrat

Original music Joan Cambon

Sound design Stéphane Ley

Costumes Sylvie Marcucci

Research and adaptation Taïcyr Fadel

Technical direction Arno Veyrat

Stage Mickaël Godbille, Albin Chavignon, Thomas Dupeyron (in alternation)

Light manager Carole China, Olivier Dupré (in alternation)

Sound manager Joël Abriac, Edouard Heneman (in alternation)

Set construction Pierre Dequivre and Atelier La fiancée du pirate

Fly machinery Marc Bizet

Production of the tours Compagnie 111 – Aurélien Bory :

Head of Production Florence Meurisse

Production manager Clément Séguier-Faucher

Production of the Groupe acrobatique de Tanger Scènes du Maroc :

Production assistance Sanae El Kamouni

Press Plan Bey Agency

EXECUTIVE PRODUCTION UNTIL JUNE 30, 2014 Grand Théâtre de Provence

PRODUCTION SINCE JULY 1, 2014 compagnie 111- Aurélien Bory

COPRODUCTION Grand Théâtre de Provence – Aix-en-Provence, Marseille – Provence 2013 – Capitale européenne de la culture, compagnie 111 – Aurélien Bory, Scènes du Maroc, Les Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg, Le Grand T théâtre de Loire-Atlantique – Nantes, Le Volcan scène nationale du Havre, Théâtre du Rond-Point – Paris, CIRCa Pôle national des arts du cirque Auch Gers Midi-Pyrénées, Agora Pôle national des arts du cirque – Boulazac Aquitaine, La Filature scène nationale – Mulhouse.

With the support from Conseil Général des Bouches-du-Rhône – Centre départemental de créations en résidence, Fondation BNP Paribas, Assami, Deloitte and Fondation d’entreprise Deloitte.

With the help of L’Usine, scène des arts de la rue et de l’espace public – Tournefeuille Toulouse Métropole

Scènes du Maroc benefits from the support from Fondation BNP Paribas, Fondation BMCI and Institut Français du Maroc.