de page

Without Object

About Men and Machines

Art does not progress, is not efficient, cannot be measured and proves nothing.

We are living in a new era, where the relationship between human beings and technology is increasingly widespread. Where once there existed an indisputable, clear frontier known to everyone, that is, the one between the inert and the living, we now see a zone of latency, dominated by two opposing questions. Will the living extend its territory in the machine, or is it technology itself which will take over the land of the living?

The dialogue between man and the machine is getting ever more profound, complex. Competition is unavoidable. The defeat of Kasparov and since then all the breakthroughs in information technology, robotics, show us that the machine is getting better at everything. The appearance of efficient prostheses and technological combinations is changing the world of sport. Man – and his two realities, body and thought – is no longer alone.

Automated core package assembly – © Laempe

After measuring up to and dominating then overcoming animals, he is now expected to match his performance to that of another type, the robot. It is likely that in this area man will be forced to technologise, whereas the machine is already becoming humanised. And it is permissible to think that in the near future, man and the robot may hybridise. Sans Objet [Purposeless] proposes this impossible encounter, that of a man and an industrial robot.

Beyond the search for performance, does the relationship between the man and the machine become purposeless? What do they have to say to each other, the man and the industrial robot, other than the tasks that usually occupy them? Aside from any goal, any function, the dance between the body of the man and that of the machine gives rise to a mechanical theatre in terms of the sensitive, between human frailty and the power of the articulated metallic arm.

Placed in the centre, in the middle of a vacuum, completely outside its industrial context, the robot becomes useless. And in its lost function doesn’t it remind us of the nature of art: to be absolutely purposeless?

A further emblem of our time… Everything which can be mechanized is mechanized. The result: our recognition of that which can not be mechanized.

Oskar Schlemmer

One should perhaps eliminate the living being from the stage.

Maurice Maeterlinck

Dance with the robot

02 March 2010

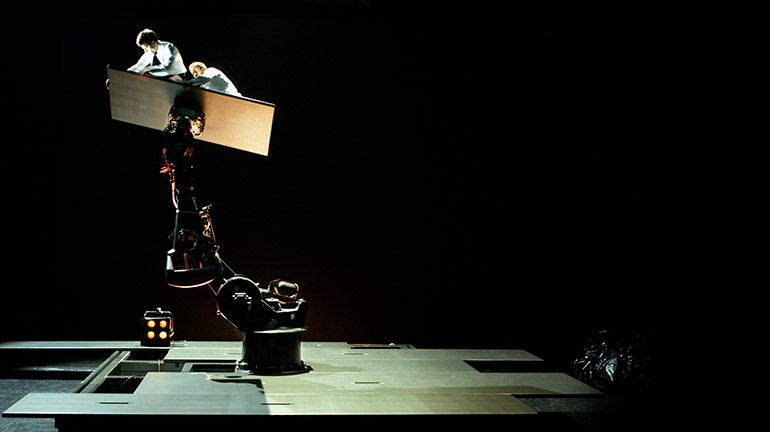

The stage is bathed in shadows. Light reflects off a sheet stretched out like a lake in the moonlight. Suddenly, something stirs beneath it. What is it? What? The shape that is sketching itself out? It could be Loïe Fuller making her giant veils soar, or a penitent clad in a hood… We can clearly see a body topped with a head, which sways itself in the giant movements of a solitary pavane dance.

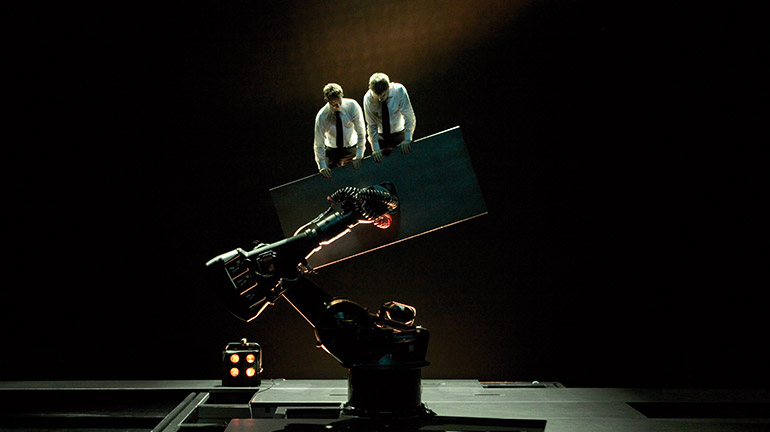

Two men appear, fresh and smart in their white shirts and ties. It’s impossible to resist: they want to know what this great totem is that dances before them. Under the sheet, a robot appears, one of those that were used in the automobile industry in the 1970s. Without an object – here we have but two men and not the slightest bit of car bodywork.

The meeting is tense. The robot grabs the head of one man and buries the other. Both seem to understand that there are ways and means to tame such a beast. Curiosity, the need to adapt. They test it, sit astride it, make movements that copy its strange lines. The machine sets a tempo, then launches them into a combat-dance, moving the ground out from beneath their feet, creating holes and walls, and cutting bodies in two. This ends after an hour and a quarter with a shower of stars.

Aurélien Bory has succeeded, once more, in playing the magician. There is nothing heavy or didactic in this inconceivable pas de trois. Humour, a ton of ideas and a dose of incongruity make this burlesque meeting between man and technology a contemporary digression on Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times.

Ariane Bavelier

The function of Art is to disturb. Science reassures.

George Braque

Interview

Your work could be defined as a crisscrossing of theatre, stage set (or performance), and circus. Do you think that this makes it difficult for the public to get the gist?

Not knowing what you are going to see is certainly one of the best ways of going to the theatre. In other words, going in a state of open-mindedness and acceptance of a new art form, without any preconceived ideas. In my productions, I try to leave spectators a lot of leeway. They themselves complete the work through an association of ideas, through their own references, through recognition and experience and through everything that influences the way they appropriate what they are seeing. It is also necessary to shake things up, to stimulate people’s imaginations. This is what I’m aiming at when I take things out of their usual context. In fact this is where Sans objet starts: taking an industrial robot and putting it on stage – a 1970s robot from the automotive industry. It was the first robot used by people, a sort of starting point of this new relationship. In its own context it has a definite use whereas on stage it loses it. It becomes “objectless”, useless, and our view of it therefore changes. It becomes the receptacle and the mirror of our projections. I see theatre a bit like that.

You often refer to your players as actors and yet they don’t utter a word and have no text.

When I say actor, I’m thinking of action. An actor is someone who is in action. In Sans objet, the actor uses his body as the main instrument for action. And on this basis dialogue with the robot is played out because the robot also has a body, an articulated arm and six axes capable of movement around itself. Generally speaking, I think that all means of action can be used on stage and, in theatre, I don’t perceive a hierarchy between text and other means of action.

In Sans objet, the robot, which is omnipresent, appears as incredibly dominant, to the point of always posing a potential threat to the players. This encounter between mankind and, seemingly insurmountable elements, already struck me in Les sept planches de la ruse. Is this confrontation of scale something that interests you particularly?

In actual fact, I try to get mankind to meet head-on with something that is totally unfamiliar by using a specific space or an object placed on stage to which I add the capacity of movement and action. The idea of the robot came from my contemplation about theatre and the animated object. It combines Kleist and his text on puppet theatre, Schlemmer in his relationship with the object and even Meyerhold, and his constructivism. In each case there is the notion of a juxtaposition of the living and of the inert, as if this confrontation revealed a secret. And also the idea of the robot seemed important today given our relationship with technology. It is complex. We love it and we use it as much as we hate it and avoid it. It upsets our relationship with the world. These are the issues in Sans objet.

What “story” did you want to tell, if you had an appropriate formulation?

The story would be: robots and men, what have they got to tell? It could also be mankind’s capacity to adapt or else the unexpected emergence of beauty, or maybe primitive forms in technology or else the future of humankind after humankind or else the simple pleasure of the use of form.

Sans objet, which I experienced at its opening in Vidy-Lausanne, is both funny and disturbing. At first, the human body comes across as technically efficient and the robot as sensitive which lends a burlesque and fantasy-like (or poetic) vocabulary to things. Then the whole thing subtly glides towards a terrifying dehumanisation and the machine ends up giving a clear demonstration of its physical power and force. Was this idea about friction between humour and tension already there at the start?

Yes. I tried to widen the scope to get more contrast between scenes. Humour operates like a counterpoint to certain strong visual impressions that are produced by stage-setting or lighting within a rigorous framework. I’m not looking for laughs but I try to get humour to increase the tension. I show men in uncomfortable, unstable and unknown situations. Burlesque action occurs to add spaciousness, a sort of “no, this is not quite serious”.

In one theatre, I was tickled to see a lot of young children of around ten accompanied by their parents. Is this something that touches you? Something you planned?

Let’s say that my shows can been seen by children. I pay special attention to their reactions. There isn’t any interfering embarrassment. You don’t doubt their sincerity. I never put on shows for the children but I am delighted when I see a few of them in the audience. I consider them as my allies.

In your opinion then, is man’s relationship with technology or machines that worrying for the future?

No. I wouldn’t say that. But we are living in a time when we can’t quite imagine our future. Maybe it comes from the fact that ten years ago the year 2000 didn’t happen. All our projections about progress, technology and the future just went for a burton. We have a sharpened awareness of our finiteness. So we have to dream different dreams.

by Christophe Lemaire, Journal du Théâtre de la Ville, janvier 2010

Distribution

With performers Pierre Cartonnet & Nicolas Lourdelle

Design, scenography and direction Aurélien Bory

Creation of roles Olivier Alenda, Pierre Cartonnet

Robot operator and programmer Tristan Baudoin

Original music Joan Cambon

Lighting design Arno Veyrat

Artistic collaboration Pierre Rigal

Director’s assistant Sylvie Marcucci

Sound Stéphane Ley

Costume design Sylvie Marcucci

Set design and construction Pierre Dequivre

Screen accessories Frédéric Stoll

Scenic painting Isadora de Ratuld

Masks Guillermo Fernandez

General technic Arno Veyrat

Sound technic Stéphane Ley or Joël Abriac

Light engineer Arno Veyrat or Mallory Duhamel

Stage manager Tristan Baudoin

Head of Production Florence Meurisse

Production manager Clément Séguier-Faucher

Press Plan Bey Agency

PRODUCTION Compagnie 111 – Aurélien Bory

COPRODUCTION ThéâtredelaCité – CDN Toulouse Occitanie, Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne, Théâtre de la Ville-Paris, La Coursive-Scène nationale La Rochelle, Agora-Pôle national des arts du cirque de Boulazac, Le Parvis-Scène nationale Tarbes-Pyrénées

With the help of London International Mime Festival, L’Usine Centre national des arts de la rue et de l’espace public – Tournefeuille Toulouse Métropole

Residency : ThéâtredelaCité – CDN Toulouse Occitanie.

Compagnie 111 – Aurélien Bory is under funding agreement with the Regional Directorate for Cultural Affairs Occitanie / French Ministry of Culture and Communication, Region Occitanie / Pyrénées – Méditerranée and the City council of Toulouse. It is supported by the Departmental Council of Haute-Garonne.